According to a tech expert, Google Chrome has evolved into spy software

You open your browser to browse the Internet. Do you realize who is staring back at you?

During a recent week of Web browsing, I looked beneath the hood of Google Chrome and discovered that it had brought along a few thousand buddies. Shopping, news, and even government websites surreptitiously tagged my browser, allowing ad and data businesses to follow me throughout the Web.

This was made feasible by the Web’s most omnipotent snooper: Google. From the inside, the Chrome browser resembles spying software.

Recently, I’ve been studying the hidden life of my data, doing experiments to uncover what technology is up to behind the veil of privacy regulations that no one reads. It turns out that allowing the world’s largest advertising corporation to create the most popular Web browser was about as wise as allowing children to manage a candy store.

It prompted me to abandon Chrome in favor of a new version of Mozilla’s Firefox, which has default privacy safeguards. Switching was less of a hassle than you may think.

My Chrome vs. Firefox tests uncovered a personal data heist of epic proportions. During a week of desktop Web browsing, I discovered 11,189 requests for tracker “cookies” that Chrome would have let to enter my machine but were automatically denied by Firefox. These are the hooks that data companies, including Google, use to track the websites you visit in order to develop profiles of your interests, income, and personality.

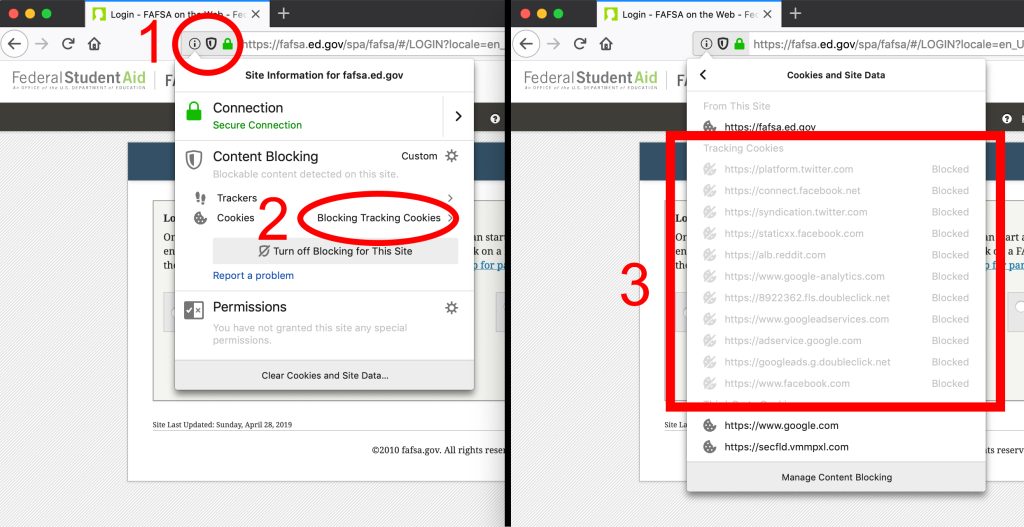

Even on websites that you would think would be private, Chrome welcomed trackers. I observed Aetna and the Federal Student Aid website setting Facebook and Google cookies. Every time I accessed the insurance and lending service log-in pages, they secretly informed the data titans.

That’s not even the half of it.

Examine your Chrome browser’s upper right corner. Is there a photograph or a name in the circle? If you are, you are logged in to the browser, and Google may be using your Web activity to target advertisements. Don’t remember signing in? Neither did I. When you use Gmail, Chrome now does this automatically.

Chrome is even more nefarious on your phone. When you make a search on Android, Chrome broadcasts your location to Google. (If you disable location sharing, your coordinates are still sent out, but with reduced accuracy.)

Firefox isn’t ideal; it still defaults to Google searches and allows some tracking. However, it does not share surfing data with Mozilla, which does not gather data.

Web snooping is at best inconvenient. Cookies are what allow a pair of pants you look at on one site to follow you around in advertising on other sites. More fundamentally, your Web history, like the color of your underwear, is your own concern. Allowing anyone to acquire that data opens it up to abuse by bullies, spies, and hackers.

In an interview, Google’s product managers informed me that Chrome prioritizes privacy options and controls, and that they’re working on additional ones for cookies. However, they also stated that they must strike the proper balance with a “healthy Web environment” (read: ad business).

According to Firefox’s product management, privacy is not a “option” that can be confined to controls. They’ve declared war on monitoring, beginning this month with “improved tracking protection,” which by default prevents inquisitive cookies on new Firefox installations. But, in order to succeed, Firefox must first persuade consumers to care enough to overcome the inertia of switching.

It’s the story of two browsers, as well as the competing interests of the firms that create them.

The cookie war

Chrome and Firefox were competing with Microsoft’s lumbering behemoth Internet Explorer a decade ago. Chrome, an upstart, solves actual customer concerns by making the Web safer and quicker. It now controls more than half of the market.

However, many of us have recently recognized that our privacy is also a key worry on the Internet — and Chrome’s goals no longer always appear to be aligned with ours.

This is most obvious in the cookie war. These code snippets can perform useful functions such as remembering the contents of your shopping cart. However, many cookies now belong to data firms, who use them to tag your browser so that they can trace your path like crumbs in the forest.

Third-party tracking cookies can be discovered on 92 percent of websites, according to one study. The Washington Post website uses over 40 tracker cookies, which the firm stated in a statement are used to deliver better-targeted ads and track ad performance.

You can also find them on non-ad-supported websites: Both Aetna and the FSA service stated that the cookies on their websites aid in the measurement of their own external marketing initiatives.

The entire advertising, publishing, and IT industries are to fault for this disaster. But what role does a browser play in safeguarding us from programs that does nothing more than spy on us?

Mozilla released a version of Firefox in 2015 that includes anti-tracking technology that was enabled only in its “private” browsing mode. That’s what it triggered this month on all websites after years of testing and tweaking. This isn’t about blocking adverts; they still appear. Instead, Firefox parses cookies to determine which to maintain for key site features and which to block for spying.

In 2017, Apple’s Safari browser, which is used on iPhones, began adding “intelligent tracking protection” to cookies, employing an algorithm to determine which ones were harmful.

Chrome, for the time being, remains open to all cookies by default. Google revealed a new attempt last month to force third-party cookies to properly self-identify, and stated we should expect additional controls for them once it is implemented. However, it refused to provide a date or specify whether it would default to stopping trackers.

I’m not going to hold my breath. Google, through its Doubleclick and other ad businesses, is the world’s largest cookie manufacturer – the Mrs. Fields of the Web. It’s difficult to picture Chrome ever severing Google’s revenue stream.

“Cookies have a role in user privacy, but a narrow focus on cookies obscures the larger privacy conversation because it’s just one way for users to be monitored across sites,” said Ben Galbraith, Chrome’s product management director. “This is a complex issue, and simple, blunt cookie blocking solutions force trackers into more obfuscated techniques.”

Other tracking methods exist, and the privacy arms race will intensify. However, claiming that things are too complicated is another way of avoiding action.

“Our perspective is to address the most serious issue first, but to foresee where the ecosystem may evolve and focus on defending against other things as well,” said Peter Dolanjski, Firefox’s product lead.

Both Google and Mozilla have stated that they are striving to combat “fingerprinting,” which is a method of sniffing out other marks on your machine. Firefox is actively evaluating its capabilities and intends to make them available soon.

Making the Change

Choosing a browser is now about more than simply speed and ease; it’s also about data defaults.

True, Google often asks consent before acquiring data and provides a plethora of controls to opt out of tracking and targeted advertising. However, its controls frequently feel like a shell game that leads to us providing more personal information.

When Google quietly began signing Gmail users into Chrome last fall, I felt duped. Google claims that the Chrome update did not cause anyone’s browsing history to be “synced” unless they specifically opted in — but mine was being transferred to Google and I don’t recall ever asking for further surveillance. (You may disable Gmail auto-login by searching for “Gmail” in Chrome settings and unchecking “Allow Chrome sign-in.”)

Following the sign-in transition, Johns Hopkins associate professor Matthew Green made headlines in the computer science field when he announced on his blog that he was done with Chrome. “I lost faith,” he admitted. “It merely takes a few minor changes to make it exceedingly unfavorable to privacy.”

There are methods to defang Chrome that are far more involved than simply utilizing “Incognito Mode.” However, switching to a browser that is not controlled by an advertising company is significantly easier.

Like Green, I’ve chosen Firefox, which is compatible with phones, tablets, PCs, and Macs. On Macs, iPhones, and iPads, Apple’s Safari is likewise a strong alternative, and the niche Brave browser goes even farther in its attempt to disrupt the ad-tech industry.

What is the cost of switching to Firefox? It’s free, and switching browsers is far easier than switching phones.

In 2017, Mozilla released Quantum, a new version of Firefox that was significantly faster. In my tests, it felt nearly as quick as Chrome, while benchmark tests revealed that it can be slower in some situations. Firefox claims to be better at managing memory if you use a lot of tabs.

When you switch, you’ll have to migrate your bookmarks, and Firefox provides features to assist you. If you use a password manager, changing your passwords is simple. Most browser add-ons are also available, albeit you might not locate your favorite.

Mozilla faces numerous hurdles. The nonprofit is well-known among privacy advocates for its prudence. It took a year longer than Apple for cookie blocking to become the default setting.

As a charity, it makes money when users conduct browser searches and click on advertising, which means Google is its primary source of revenue. Mozilla’s CEO says the company is looking into new paid privacy offerings to diversify its revenue.

The greatest danger is that Firefox will eventually run out of steam in its battle with the Chrome giant. Despite having roughly 10% of the desktop browser market, prominent sites may decide to discontinue support, leaving Firefox scrambling.

Let us hope for another David and Goliath conclusion if you value privacy.