Jupiter is bigger than some stars, so why don’t we have a second Sun?

The tiniest main-sequence star known to exist in the Milky Way galaxy is a real pixie.

It is a red dwarf called EBLM J0555-57Ab. It is 600 light-years away. It is just a little bit bigger than Saturn, with a mean radius of about 59,000 km. That makes it the smallest known star with hydrogen fusion in its core, which is what keeps stars burning until they run out of fuel.

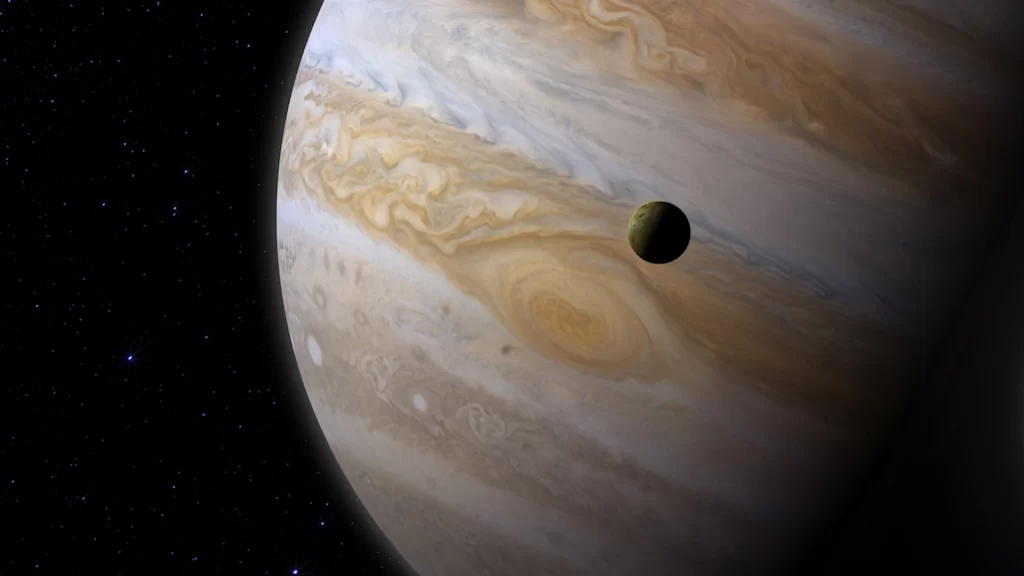

There are two things bigger than this tiny star in our Solar System. One is, of course, the Sun. The other is Jupiter, which has a mean radius of 69,911 kilometers and looks like a big scoop of ice cream.

So why isn’t Jupiter a star but a planet?

The short answer is that Jupiter doesn’t have enough mass to turn hydrogen into helium. EBLM J0555-57Ab has about 85 times the mass of Jupiter, which is about as light as a star can be. If it were any lighter, it wouldn’t be able to fuse hydrogen either. But if the Sun and planets were different, could Jupiter have turned into a star?

You don’t know how much Jupiter and the Sun are alike.

Even though Jupiter is not a star, it is still a Big Deal. It has 2.5 times as much mass as all the other planets put together. Just that, since it is a gas giant, it has a very low density of 1.33 grams per cubic centimeter, which is about four times less than Earth.

But it’s interesting to think about how much Jupiter and the Sun are alike. 1.41 grams per cubic centimeter is how dense the Sun is. And the two things are very similar in how they are made. About 71% of the Sun’s mass is made up of hydrogen and 27% is made up of helium. The rest is made up of small amounts of other elements. About 73% of Jupiter’s mass is made up of hydrogen, and about 24% is made up of helium.

Jupiter is sometimes called a failed star because of this

But it’s still unlikely that Jupiter would even get close to becoming a star if left to its own devices.

So, you can see that stars and planets are made in very different ways. When a dense knot of material in an interstellar molecular cloud collapses under its own gravity, it spins as it goes through a process called “cloud collapse.” This is how stars are made. As it spins, it pulls more matter from the cloud around it and puts it into a ring called an accretion disc.

As the mass, and therefore the gravity, grows, the core of the baby star is squeezed tighter and tighter, making it hotter and hotter. At some point, it gets so tight and hot that the core catches fire and thermonuclear fusion begins.

Based on what we know about how stars form, once a star is done adding material, there is a lot of accretion disc left over. These are the things that make up the planets.

Astronomers think that this process, called “pebble accretion,” starts with tiny pieces of icy rock and dust in the disc of a gas giant like Jupiter. As these pieces of matter circle the baby star, they start to bump into each other and stick together with static electricity. At some point, these growing clumps get big enough, about 10 Earth masses, that their gravity can pull more and more gas from the disc around them.

From there, Jupiter slowly got bigger and bigger until it reached its current size, which is about 318 times the size of Earth and 0.001 times the size of the Sun. Once it had eaten everything it could find, which was a long way from the mass needed for hydrogen fusion, it stopped growing.

So, Jupiter was never even close to getting big enough to become a star. Jupiter has a similar make-up to the Sun, not because it was a “failed star,” but because it was made from the same cloud of molecular gas that made the Sun.

The real stars who failed

There is another kind of thing that can be called a “failed star.” These are brown dwarfs, and they fill the space between gas giants and stars.

Starting at more than 13 times the mass of Jupiter, these objects are big enough to support core fusion of deuterium instead of normal hydrogen. This is also called “heavy” hydrogen because its nucleus has a proton and a neutron instead of just a single proton. Both the temperature and pressure at which it can fuse are lower than those at which hydrogen can fuse.

Because it happens at a lower mass, temperature, and pressure, deuterium fusion is an intermediate step on the way for stars to reach hydrogen fusion as they continue to gain mass. But some things never get that heavy. These things are called brown dwarfs.

After their existence was confirmed in 1995, scientists didn’t know for a while if brown dwarfs were underachieving stars or overambitious planets. However, several studies have shown that they form the same way stars do, from cloud collapse instead of core accretion. Some brown dwarfs are even too small to burn deuterium, making them look like planets.

Jupiter is very close to the lowest mass limit for cloud collapse. The smallest mass of an object that collapsed from a cloud is thought to be about one Jupiter mass. So, Jupiter could be thought of as a failed star if it formed when clouds broke apart.

But data from NASA’s Juno probe show that Jupiter may have had a solid core in the past, which fits better with the core accretion theory of how it formed.

Modelling suggests that the most massive planet that can form by adding material to its core is less than 10 times the mass of Jupiter. This is just a few Jupiter masses away from the mass of a star that can fuse deuterium.

So Jupiter isn’t a star that failed. But thinking about why it isn’t a star can help us figure out how the universe works. Jupiter is also a striped, stormy, swirly, butterscotch-colored wonder on its own. And we humans might not have been able to live without it.

But that’s a different story that will have to wait for another time.