Scientists have figured out how and when our sun will die, and it will be spectacular

How will our Sun appear after it dies? Scientists have predicted what the end of our Solar System will look like and when it will occur. And humans will not be present to witness the ultimate act.

Previously, astronomers predicted that it would form a planetary nebula – a bright bubble of gas and dust – until data revealed that it would have to be much larger.

In 2018, an international team of astronomers reversed the equation and discovered that a planetary nebula is indeed the most likely solar corpse.

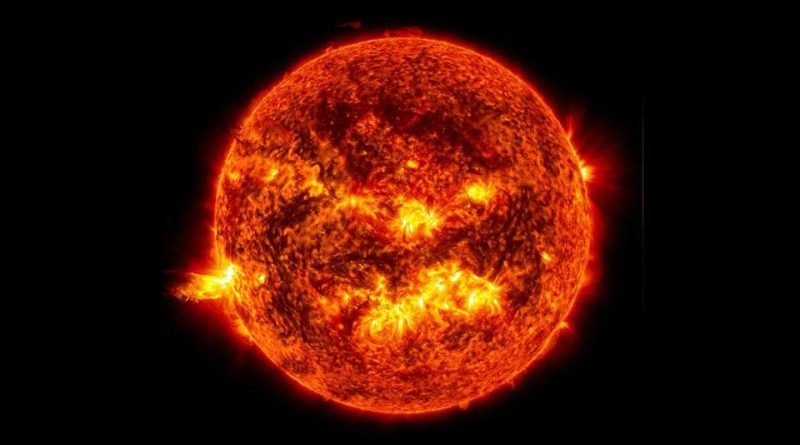

The Sun is approximately 4.6 billion years old, based on the ages of other Solar System objects that originated around the same period. Astronomers believe that based on observations of other stars, it will die in around 10 billion years.

Of course, there will be other things that happen along the way. The Sun will become a red giant in around 5 billion years. The star’s core will diminish, but its outer layers will extend out to Mars’ orbit, engulfing our planet in the process. If it’s still standing.

One thing is certain: we will not be alive by that time. In fact, unless we find a way off this rock, humanity has just around 1 billion years left. This is due to the Sun’s brightness increasing by around 10% per billion years.

That may not seem like much, but the rise in brightness will be the end of life on Earth. Our oceans will evaporate, and the surface will become too hot to produce new water. We’ll be about as kaput as it gets.

What comes after the red giant has been difficult to predict. Several prior studies have discovered that for a brilliant planetary nebula to emerge, the original star must have been up to twice the mass of the Sun.

The 2018 study, on the other hand, employed computer modeling to establish that our Sun, like 90% of all stars, is most likely to decline from a red giant to a white dwarf and then to a planetary nebula.

“When a star dies, it ejects a cloud of gas and dust into space, known as its envelope. The envelope can be as large as half the mass of the star. This displays the star’s core, which is running out of fuel by this stage in the star’s life, eventually turning off and dying “One of the paper’s authors, astrophysicist Albert Zijlstra of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, explained.

“Only then does the heated core cause the ejected envelope to shine brilliantly for approximately 10,000 years – a brief period in astronomy. This is what allows us to see the planetary nebula. Some are so luminous that they can be seen from tens of millions of light years away, while the star itself would have been far too faint to view.”

The data model developed by the researchers forecasts the life cycle of various types of stars in order to calculate the brightness of the planetary nebula associated with different star masses.

Planetary nebulae are quite abundant across the visible Universe, with prominent examples being the Helix, Cat’s Eye, Ring, and Bubble nebulae.

They’re called planetary nebulae not because they have anything to do with planets, but because when William Herschel discovered them in the late 18th century, they looked like planets through telescopes at the time.

Almost 30 years ago, astronomers noticed something strange: the brightest planetary nebulae in other galaxies are all around the same brightness. This means that, theoretically, astronomers may compute how far away other galaxies are by looking at their planetary nebulae.

The facts indicated that this was right, but the models contradicted it, which has perplexed experts since the discovery.

“Younger, more massive stars should produce considerably fainter planetary nebulae than older, lower mass stars. For the past 25 years, this has been a cause of contention “Zijlstra stated

“The data suggested that you could create bright planetary nebulae from low mass stars like the Sun, but the models claimed that wasn’t conceivable; anything less than around twice the mass of the Sun would produce a planetary nebula that was too faint to view.”

The 2018 models solved this difficulty by demonstrating that the Sun is near the lower limit of mass for a star capable of producing a visible nebula.

A visible nebula cannot be produced by a star with a mass less than 1.1 times that of the Sun. Bigger stars, up to three times more massive than the Sun, will form brighter nebulae.

The anticipated brightness for all the other stars in between is quite close to what has been observed.

“This is a good outcome,” Zijlstra stated. “Not only do we now have a technique to measure the presence of stars a few billion years old in distant galaxies, which is a pretty difficult range to measure, but we also know what the Sun will do when it dies!”