Can our brains really read jumbled words as long as the first and last letters are right?

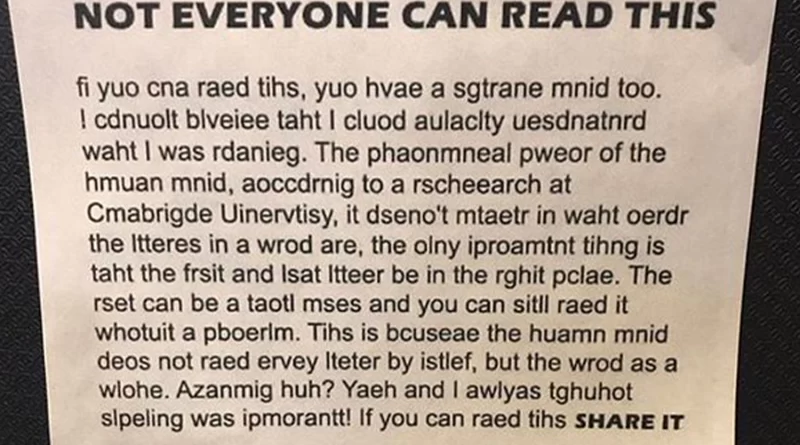

You’ve probably seen the classic piece of “internet trivia” in the picture above before. It’s been around since at least 2003.

At first glance, it looks like a good deal. It’s because you can read it, right? But even though there is some truth to the meme, the real world is always more complicated.

The meme says, based on an unnamed Cambridge scientist, that you can still read a piece of text as long as the first and last letters of each word are in the right places.

We’ve gotten the message straight again.

A study at Cambridge University found that the order of the letters in a word doesn’t matter. What’s important is that the first and last letters are in the right places. The rest can be a mess, and you will still be able to read it. This is because the mind doesn’t read each letter on its own, but rather the whole word.

In fact, there was never a Cambridge researcher (the first version of the meme spread without that part), but there is a scientific reason why we can read that jumbled text.

The name “Typoglycaemia” is a little tongue-in-cheek, and it works because our brains don’t just use what they see; they also use what we expect to see.

Researchers from the University of Glasgow found in 2011 that when something is hidden or unclear to the eye, people’s minds can guess what they think they will see and fill in the blanks.

“In reality, our brains put together a very complicated jigsaw puzzle using any pieces they can find,” researcher Fraser Smith said. “The context in which we see them, our memories, and our other senses give us these.”

But the meme is not the whole story. Matt Davis, a researcher at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at the University of Cambridge, wanted to find out more about the “Cambridge” claim because he thought he should have heard about the research before.

He was able to find out that the first demonstration of randomizing letters was done by a researcher named Graham Rawlinson. In 1976, he wrote his PhD thesis at Nottingham University on the subject.

He did 16 tests and found that, yes, people could still understand words even if the middle letters were mixed up. However, as Davis points out, there are a few things to keep in mind.

- It’s a lot easier to do with short words, probably because there are less things that can go wrong.

- Function words, like and, the, and a, that give the sentence structure tend to stay the same because they are so short. This helps the reader by keeping the structure and making it easier to guess what will happen next.

- Switching letters that are close together, like porbelm for problem, is easier than switching letters that are farther apart, like plorebm.

- Davis gives the example of wouthit vs. witohut to show that none of the words in the meme can be rearranged to make another word. This is because words like calm and clam, or trial and trail, where the only difference is where two letters are placed next to each other, are harder to read.

- All of the words pretty much kept their original sounds. For example, order became oredr instead of odrer, but the sound was the same.

- The text is pretty easy to guess.

Keeping double letters together also helps. For example, it’s much easier to figure out aoccdrnig and mttaer than it is to figure out adcinorcg and metatr.

There is evidence to suggest that ascending and descending elements also play a role and that what we recognize is the shape of a word. Mixed-case text, like alternating capital letters, is hard to read because it changes the shape of a word so much, even if all the letters are in the right place.

If you play around with this generator, you can see for yourself how randomizing the middle letters of words can make text very hard to read. Here’s what:

The adkmgowenlcent – whcih cmeos in a reropt of new mcie etpnremxeis taht ddin’t iotdncure scuh mantiotus – isn’t thelcclnaiy a rtoatriecn of tiher eearlir fidginns, but it geos a lnog way to shnwiog taht the aalrm blels suhold plarobby neevr hvae been sdnuoed in the fsrit plcae.

This one might be a little bit of a cheat, since it’s a paragraph from a ScienceAlert article about CRISPR.

The acknowledgment – which comes in a report of new mice experiments that didn’t introduce such mutations – isn’t technically a retraction of their earlier findings, but it goes a long way to showing that the alarm bells should probably never have been sounded in the first place.

Try this one out and see how it goes.

Soaesn of mtiss and mloelw ftisnflurues,

Csloe boosm-feinrd of the mrtuniag sun;

Cnponsiirg wtih him how to laod and besls

Wtih friut the viens taht runod the tahtch-eevs run

Those are the first four lines of John Keats’s poem “To Autumn.”

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run

So, there are some interesting ways our brains work when we use prediction and word shape to improve our reading skills, but it’s not as simple as that meme makes it sound.