According to science, only half of your friends like you

When you refer to someone as a friend, it goes without saying that they regard you as a friend as well – you like them, they like you, it’s a mutual thing.

However, according to a 2016 study, this is probably only true around half of the time – just half of perceived friendships are genuinely mutual, which is a concern.

The study, led by MIT academics, examined friendship ties among 84 participants aged 23 to 38 who were enrolled in a business management program.

The individuals were asked to rate their relationship with each person in the class on a scale of 0 to 5, with 0 indicating “I do not know this person,” 3 indicating “Friend,” and 5 indicating “One of my best friends.”

The researchers discovered that whereas 94% of the subjects expected their feelings to be reciprocated, just 53% of them were.

The study is constrained by its small sample size, but as Kate Murphy explains for The New York Times, the findings are comparable with data from six other friendship studies over the last decade, which included more than 92,000 respondents and found reciprocity rates ranging from 34 to 53 percent.

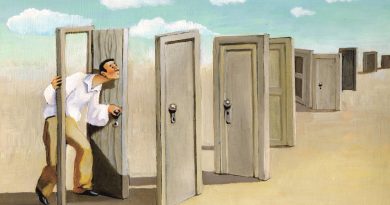

This perception gap in friendship suggests a number of serious issues, ranging from our inability to precisely define friendship and the influence this may have on our own self-image to our misconceptions about the types of people who may truly affect societal change.

While one of the team’s members, computational social science researcher Alex Pentland, believes that our inability to read people is largely due to our desperate attempt to maintain a positive self image – “We like them, they must like us.” – the concept of friendship is actually extremely difficult to define.

“Ask people to define friendship, even scholars like Mr Pentland who study it, and you’ll get an awkward silence followed by ‘er’ or ‘uh,'” Murphy says.

It wasn’t always this difficult. As the kids from everyone’s new favorite show, Stranger Things, put it: “When we’re young, the concept of friendship is quite basic.”

- A friend is someone for whom you would go to any length.

- You loan them your cool items, such as comic novels and trading cards.

- They never fail to keep their promises.

Most significantly, “Friends don’t tell lies.”

But things aren’t so straightforward in adolescence and adulthood, especially with social media marketing friendship as a commodity, which is the exact opposite of how you’re supposed to think of them.

“Treating friends like investments or commodities is antithetical to the very concept of friendship,” Ronald Sharp, an English professor at Vassar College who teaches a course on the literature of friendship, told Murphy. “It’s not about what someone can do for you; it’s about who and what the two of you become when you’re in each other’s company.”

Sharp goes on to say that in many of our connections, we spend far more time tweeting at one other than really getting out with them, which is how perceptions may become dangerously skewed.

“People have lost touch with what it means to be a friend because they are so keen to maximize the efficiency of relationships,” he argues.

But don’t worry, it’s not all terrible news. According to renowned British anthropologist Robin Dunbar, if you reduce your buddies in half and wind up with five true pals who truly love you back, you’re precisely where you’re supposed to be.

According to Dunbar’s research, while 150 is the highest number of social interactions the ordinary human can maintain with any degree of stability, we can only maintain five close friendships at the same time.

“People may claim to have more than five, but you can bet they aren’t high-quality friendships,” he told The Times.

So don’t worry if your social media friend lists aren’t as large as your real-life friends’ – chances are, most of us are quite equal when it comes to true connections.

And don’t trust what you hear about those with the most followings wielding the most power, because what’s the point if half of them are unlikely to be reciprocated?

“We shouldn’t assume that people with a large number of social ties are ‘influencers,'” writes Pentland for the Harvard Business Review.

Such people are no better, and frequently worse, than typical people at wielding social power. Our findings imply that this is because many of those linkages are either not reciprocal or go in the wrong direction, making effective persuasion impossible.

So, if you’re looking for someone who can influence others and cause societal change, look for groups of people who have a similar number of friends and a lot of friends in common, adds Pentland.

Because their connections will be far more genuine than anything in Kim Kardashian’s feed.