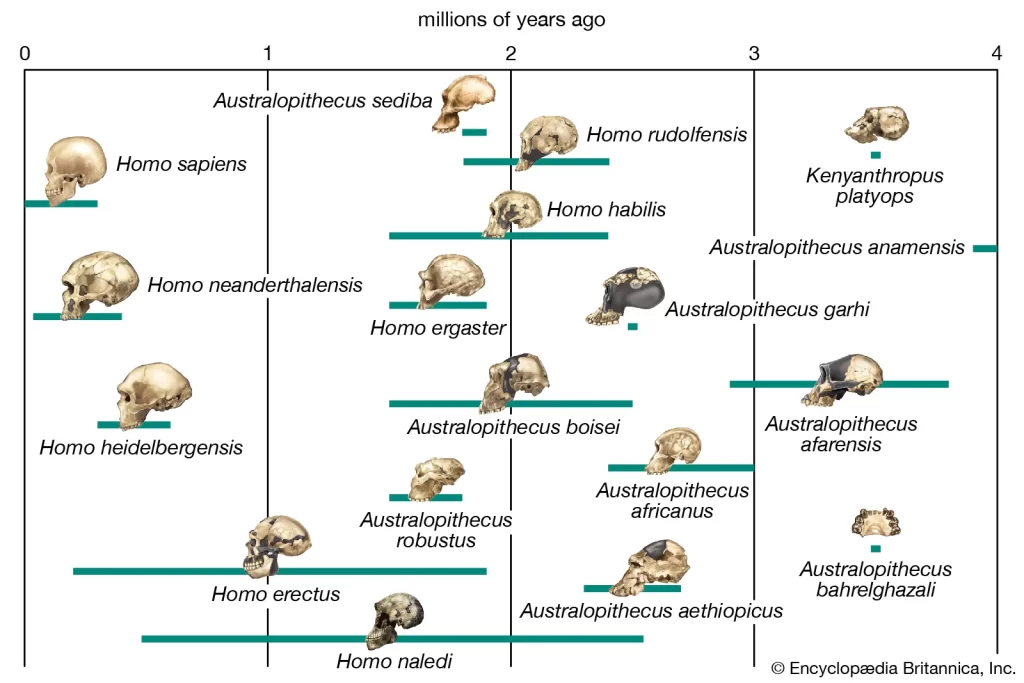

9 Human Species Once Walked the Earth. There is now only one. Did We Kill the Others?

Nine different human species roamed the Earth 300,000 years ago. There is now only one. Homo neanderthalensis were stocky hunters who adapted to Europe’s frigid steppes.

Denisovans dwelt in Asia, whereas Homo erectus and Homo rhodesiensis thrived in Indonesia and central Africa, respectively.

Homo naledi in South Africa, Homo luzonensis in the Philippines, Homo floresiensis (“hobbits”) in Indonesia, and the mysterious Red Deer Cave People in China all thrived alongside them.

Given how quickly we discover new species, more are very certainly on the way.

They had all vanished by 10,000 years ago. The extinction of these other species is comparable to a mass extinction. However, there is no evident environmental disaster driving it, such as volcanic eruptions, climate change, or asteroid impact.

Instead, the timing of the extinctions shows that they were triggered by the expansion of a new species, Homo sapiens, which evolved 260,000-350,000 years ago in Southern Africa.

The migration of modern humans out of Africa has resulted in a sixth mass extinction, a more than 40,000-year catastrophe spanning the demise of Ice Age creatures to the devastation of rainforests today. But were other humans the first to perish?

We are a hazardous species in our own right. Woolly mammoths, ground sloths, and moas were all hunted to extinction by humans. We altered over half of the planet’s surface area by destroying plains and forests for farming. We changed the climate of the globe.

However, we pose the greatest threat to other human populations because we compete for resources and land.

From Rome’s destruction of Carthage to the American conquest of the West and the British colonisation of Australia, history is replete with examples of people fighting, displacing, and wiping out other communities for territory. Recent genocides and ethnic cleansing have also occurred in Bosnia, Rwanda, Iraq, Darfur, and Myanmar.

A capability for and proclivity to commit genocide, like language or tool usage, is undoubtedly an inherent, instinctive element of human nature. There’s little reason to believe that early Homo sapiens were less territorial, violent, and intolerant – in other words, less human.

Optimists have portrayed early hunter-gatherers as peaceful, virtuous savages, arguing that it is our civilization, not our character, that causes violence. However, field investigations, historical narratives, and archaeology all reveal that battle was violent, pervasive, and devastating in prehistoric communities.

Neolithic weaponry like clubs, spears, axes, and bows were lethal when paired with guerrilla tactics like raids and ambushes. In these societies, violence was the major cause of death among men, and wars had higher mortality rates per person than World Wars I and II.

This brutality is centuries old, as evidenced by ancient bones and artifacts. Kennewick Man, a 9,000-year-old North American, has a spear point implanted in his pelvis. The Nataruk site in Kenya, which dates back 10,000 years, records the horrible killing of at least 27 men, women, and children.

It’s doubtful that other human species were substantially more peaceful. The presence of cooperative violence in male chimps shows that war existed before humans.

Trauma patterns in Neanderthal skeletons are compatible with fighting. However, sophisticated weapons provided Homo sapiens a military advantage. Early Homo sapiens’ armory most likely included projectile weapons such as javelins and spear throwers, as well as throwing sticks and clubs.

Complex tools and culture would have also allowed humans to harvest a wider variety of animals and plants, feeding larger tribes and providing our species a strategic advantage in numbers.

The ultimate tool

However, cave paintings, sculptures, and musical instruments suggest something considerably more dangerous: an advanced capacity for abstract cognition and communication. Our ultimate weapon may have been our ability to collaborate, plot, strategize, manipulate, and deceive.

The inadequacy of the fossil record makes it difficult to examine these hypotheses. However, in Europe, the only continent with a relatively comprehensive archaeological record, fossils suggest that Neanderthals perished within a few thousand years after our arrival.

Traces of Neanderthal DNA in some Eurasian populations demonstrate that we did not simply replace them after they became extinct. We met and fell in love.

Other contacts with archaic people are documented in DNA. Denisovan DNA can be found in East Asian, Polynesian, and Australian populations. Many Asians have DNA from another species, possibly Homo erectus. African genomes contain DNA from yet another extinct species. The fact that we interbred with these other species demonstrates that they vanished only after meeting us.

But why would our forefathers annihilate their relations, resulting in a global extinction – or, perhaps more precisely, a mass genocide?

Population expansion is the answer. Humans, like all other species, reproduce at an exponential rate. We have historically doubled our population every 25 years if left unchecked. We had no predators until humans became cooperative hunters.

Populations grew to utilize the available resources in the absence of predation and little family planning beyond delayed marriage and infanticide.

Further expansion, or food shortages caused by drought, hard winters, or overharvesting resources, would inevitably lead to warfare amongst tribes over food and foraging territory. Warfare became, perhaps, the most essential check on population expansion.

Our annihilation of other species was most likely not a planned, organized effort like that of civilisations, but rather a war of attrition. The eventual result, on the other hand, was just as definitive. Modern humans would have worn down their opponents and taken their territory raid after raid, ambush by ambush, valley by valley.

However, the extinction of the Neanderthals took thousands of years. This was due in part to the fact that early Homo sapiens lacked the advantages of later conquering civilisations, such as massive numbers supported by farming and epidemic diseases such as smallpox, flu, and measles that ravaged their opponents.

While the Neanderthals did not win the war, they must have fought and won numerous battles against us, implying a level of intelligence comparable to our own.

We now look up at the stars and wonder if we are the only ones in the cosmos. In fantasy and science fiction, we imagine what it might be like to encounter other intelligent species that are similar to us but not identical to us. It’s heartbreaking to think that we once did, and that as a result, they’ve vanished.