Here is what magic mushrooms do to your body and brain

There is evidence that tripping on magic mushrooms could actually free the mind. Several studies, including two promising clinical trials that took place recently, suggest that psilocybin, the psychoactive part of shrooms, may be able to help relieve severe anxiety and depression.

Still, because they are illegal and on Schedule 1, which means they have “no accepted medical use,” it’s been hard for scientists to figure out what they can and can’t do.

Here are a few ways we know shrooms can affect your brain and body:

Shrooms can make you feel good

The National Institute on Drug Abuse says that magic mushrooms can make you feel relaxed in the same way that low doses of marijuana do.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse says that most of the effects of shrooms come from the way they affect neural highways in the brain that use the neurotransmitter serotonin. This is similar to how LSD and peyote work.

More specifically, magic mushrooms affect the prefrontal cortex of the brain. This is a part of the brain that controls abstract thinking, thought analysis, and perception.

Also, they can make you have hallucinations

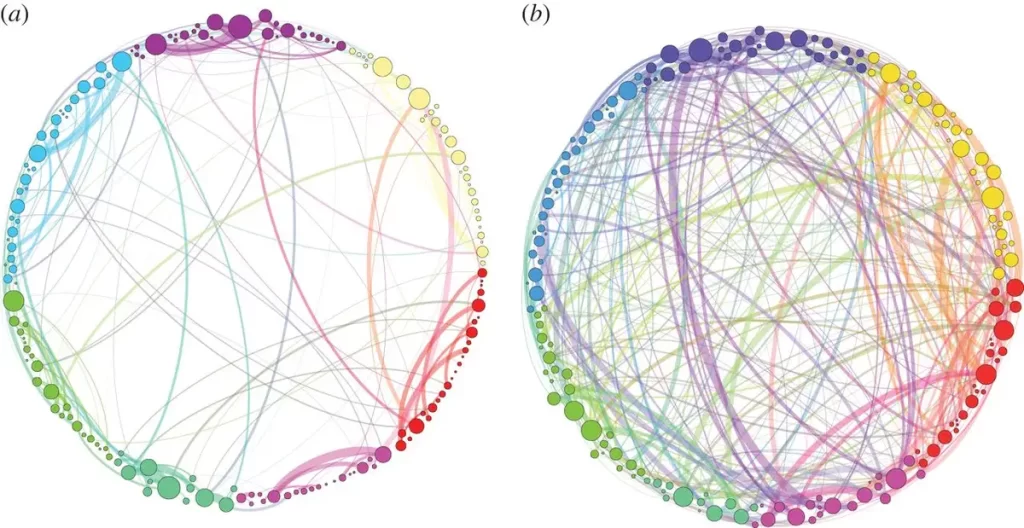

Above: A picture of the connections in the brain of a person on psilocybin (right) and a person who was given a placebo (left).

Many people say that they hear colors or see sounds. One of the first studies to link this effect to the way psilocybin changes how brain networks talk to each other was done in 2014.

When 2 milligrams of the drug was injected into a person, researchers saw new, stronger activity in several parts of the brain that normally don’t talk to each other.

The researchers made the picture above to show what they saw in the people who were given the drug, as opposed to those who were given a fake pill.

This may be the key to figuring out how shrooms could help people who are depressed

David Nutt, a neuroscientist at Imperial College London who wrote a 2012 study on psilocybin, also found that the drug changed the way people’s brains worked.

While some parts got louder, others got quieter. This happened in a part of the brain that is thought to help us keep our sense of self.

Nutt thinks that people with depression have too strong connections between brain circuits in this “sense of self” area. “When people are depressed, their brains are too linked together,” Nutt told.

But, the thinking goes, letting go of these connections and making new ones could bring a lot of relief.

A five-year study of the drug shows that it could help treat mental illness “like surgery”

Based on the results of two controlled clinical trials that looked at how psilocybin affected people with depression and anxiety about dying, a single dose of the drug could one day be used to treat depression and anxiety effectively.

Researchers from Johns Hopkins University did the first one, and researchers from New York University did the second.

A gold standard psychiatric evaluation showed that the symptoms of depression and anxiety in 80% of the Johns Hopkins participants had gotten much better six months after the experience.

As my colleague Kevin Loria reported, the NYU team says that between 60% and 80% of its participants had less anxiety and depression 6.5 months after a single psychedelic trip.

Some researchers think that after using shrooms, they could also help relieve anxiety.

For a New York University study on how the drug might affect cancer patients with severe anxiety, researchers watched the effects of psilocybin on volunteers who were given either a pill dose of psilocybin or a placebo.

In the picture above, the steps are acted out again.

Nick Fernandez, who took part in 2014, told Aeon Magazine that his trip was an emotional journey that helped him see “a force greater than [himself].”

“Something broke inside of me,” and I “realized that all my worries, defenses, and fears were nothing to worry about.”

Jeffrey Guss, a psychotherapist at NYU, told the New Yorker that many participants had the same experience. He added, “We think of that as part of the healing process.”

But you might also feel anxious while you’re on the drug

In many of the case reports from the NYU study, participants said that during their trip, they felt very anxious and uncomfortable for a few minutes to a few hours.

Some people said they didn’t start to feel better until afterward, but even this can be very different for each person.

Your pupils could also get bigger

If you use shrooms, you might get more serotonin, which can make your pupils bigger.

And you might not know what time it is

The National Institute on Drug Abuse says that one of the side effects of taking shrooms is feeling like time has slowed down.

You might feel like you’re not in your body

Mushrooms can make you have things happen that seem real but aren’t.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse says that these kinds of “out-of-body” experiences, in which drug users might see a copy of themselves, usually start 20 to 90 minutes after taking the drug and can last for up to 12 hours.

Experiences can be different depending on how much you take, how you feel, and even where you are.

You might also feel more creative or open

A small group of healthy volunteers at Johns Hopkins were given psilocybin to make them have out-of-body experiences. The volunteers said they felt more open, creative, and appreciative of beauty.

When the researchers checked in with the volunteers a year later, nearly two-thirds of them said that the experience had been one of the most important in their lives. Nearly half of them still scored higher on a personality test of openness than they had before taking the drug.

Some users have said that their hallucinations last for a long time, which may be a sign of a rare disorder called HPPD

Since the 1960s, there have been scattered reports of something called hallucinogen persisting perception disorder. This is when hallucinations last for a long time after someone has taken a hallucinogen, usually LSD.

(There are also some anecdotal reports of this from people who have used shrooms.)

Scientists haven’t yet come up with a clear definition of HPPD, but John Halpern, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and lead author of the most recent review of HPPD, told the New Yorker that:

“It seems unavoidable,” based on 20 related studies going back to 1966, “that at least some people who have used LSD, in particular, experience persistent perceptual abnormalities that remind them of acute intoxication and can’t be explained by another medical or psychiatric condition.”